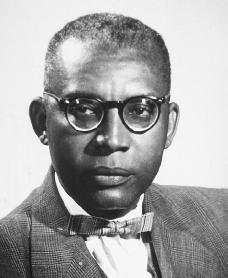

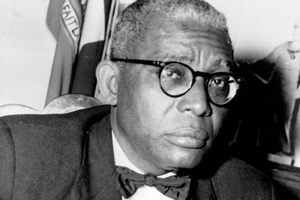

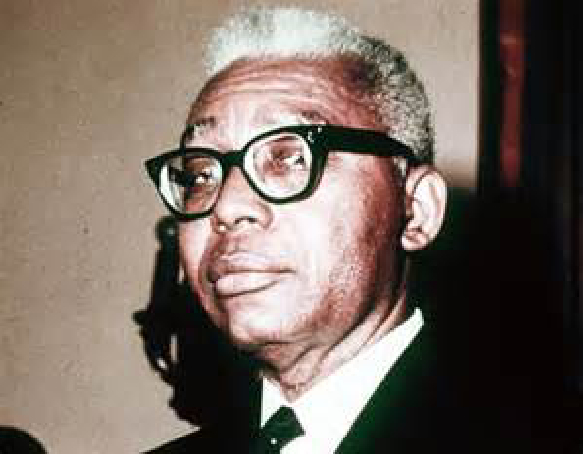

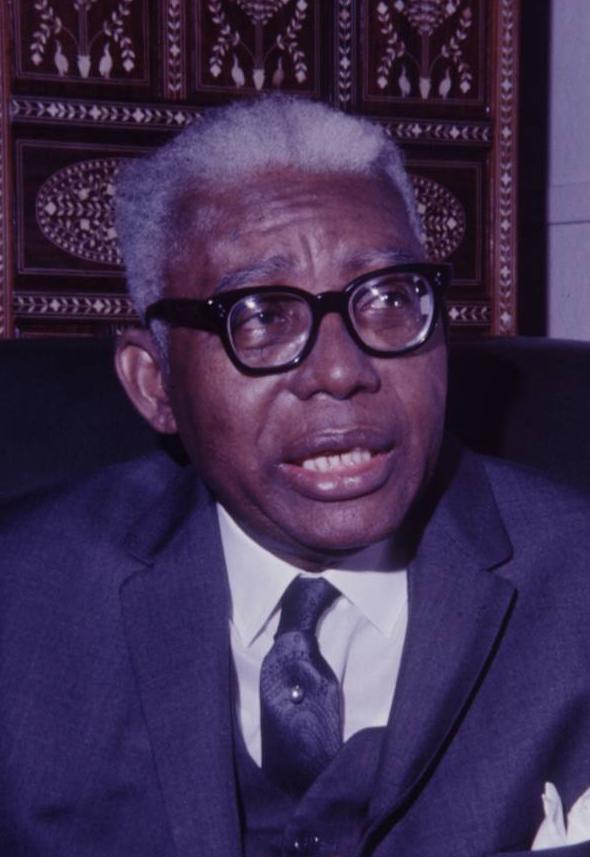

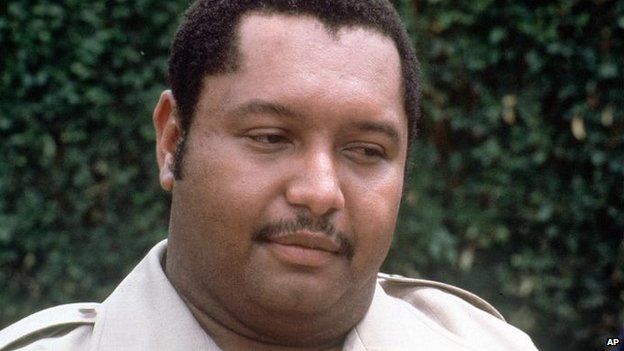

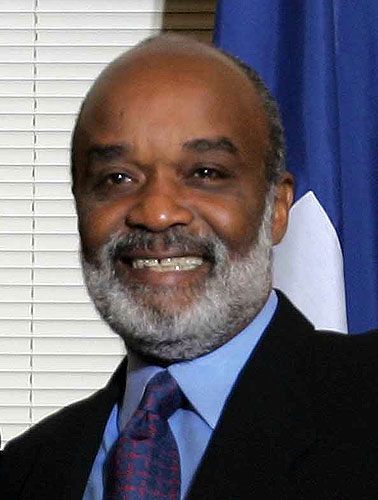

François Duvalier

| François Duvalier | |

|---|---|

|

|

| 32nd President of Haiti | |

|

In office 22 October 1957 – 21 April 1971 |

|

| Preceded by |

Antonio Thrasybule Kébreau(Chairman of the Military Council) |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Claude Duvalier |

| Minister of Public Health and Labor | |

|

In office 14 October 1949 – 10 May 1950 |

|

| President | Dumarsais Estimé |

| Preceded by |

Antonio Vieux (Public Health) Louis Bazin (Labor) |

| Succeeded by |

Joseph Loubeau (Public Health) Emile Saint-Lot (Labor) |

| Undersecretary of Labor | |

|

In office 26 November 1948 – 14 October 1949 |

|

| President | Dumarsais Estimé |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

14 April 1907 Port-au-Prince, Haiti |

| Died |

21 April 1971 (aged 64) Port-au-Prince, Haiti |

| Nationality | Haitian |

| Political party | National Unity[1][2] |

| Spouse(s) | Simone Duvalier |

| Children |

Marie?Denise Duvalier Nicole Duvalier Simone Duvalier Jean-Claude Duvalier |

| Alma mater | University of Haiti (MD) |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Religion | Vodou, excommunicated Catholic |

Early life and career[edit]

Duvalier was born in Port-au-Prince in 1907, son of Duval Duvalier, a justice of the peace, and baker Ulyssia Abraham.[8]His aunt, Madame Florestal, raised him.[6]:51 He completed a degree in medicine from the University of Haiti in 1934,[9]and served as staff physician at several local hospitals. He spent a year at the University of Michigan studying public health[6]:53 and in 1943, became active in a United States-sponsored campaign to control the spread of contagious tropical diseases, helping the poor to fight typhus, yaws, malaria and other tropical diseases that had ravaged Haiti for years.[9] His patients affectionately called him “Papa Doc”, a moniker that he used throughout his life.[10]

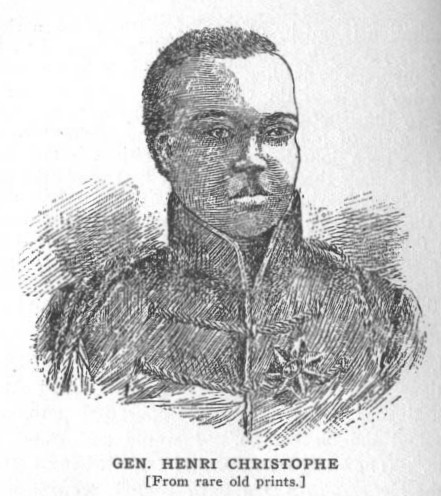

The United States occupation of Haiti, which began in 1915, left a powerful impression on the young Duvalier. He was also aware of the latent political power of the poor black majority and their resentment against the tiny mulatto elite.[11]Duvalier supported Pan-African ideals,[12] and became involved in the négritude movement of Haitian author Jean Price-Mars, both of which led to his advocacy of Haitian Vodou,[13] an ethnological study of which later paid enormous political dividends for him.[11][14] In 1938, Duvalier co-founded the journal Les Griots. In 1939, he married Simone Duvalier (née Ovide), with whom he had four children: Marie?Denise, Nicole, Simone, and Jean?Claude.[15]

Political rise[edit]

In 1946, Duvalier aligned himself with President Dumarsais Estimé and was appointed Director General of the National Public Health Service. In 1949, he served as Minister of Health and Labor, but when Duvalier opposed Paul Magloire’s 1950 coup d’état, he left the government and resumed practicing medicine. His practice included taking part in campaigns to prevent yaws and other diseases. In 1954, Duvalier abandoned medicine, hiding out in Haiti’s countryside from the Magloire regime. In 1956, the Magloire government was failing, and although still in hiding, Duvalier announced his candidacy to replace him as president.[6]:57 By December 1956, an amnesty was issued and Duvalier emerged from hiding,[16] and on 12 December 1956, Magloire conceded defeat.[6]:58

The two frontrunners in the 1957 campaign for the presidency were Duvalier and Louis Déjoie, a landowner and industrialist from the north. During their campaigning, Haiti was ruled by five temporary administrations, none lasting longer than a few months. Duvalier promised to rebuild and renew the country and rural Haiti solidly supported him as did the military. He resorted to noiriste populism, stoking the majority Afro-Haitians’ irritation at being governed by the few mulatto elite, which is how he described his opponent, Déjoie.[5]

François Duvalier was elected president on 22 September 1957. Duvalier received 679,884 votes to Déjoie’s 266,992.[17] Even in this election, however, there are multiple first-person accounts of voter fraud and voter intimidation.[6]:64

Presidency[edit]

Consolidation of power[edit]

After being elected president in 1957, Duvalier exiled most of the major supporters of Déjoie.[18] He had a new constitution adopted that year.[10]

Duvalier promoted and installed members of the black majority in the civil service and the army.[12] In July 1958, three exiled Haitian army officers and five American mercenaries landed in Haiti and tried to overthrow Duvalier; all were killed.[19] Although the army and its leaders had quashed the coup attempt, the incident deepened Duvalier's distrust of the army, an important Haitian institution over which he did not have firm control. He replaced the chief-of-staff with a more reliable officer and then proceeded to create his own power base within the army by turning the Presidential Guard into an elite corps aimed at maintaining his power. After this, Duvalier dismissed the entire general staff and replaced it with officers who owed their positions, and their loyalty, to him.[10]

In 1959, Duvalier created a rural militia, the Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale (VSN, English: National Security Volunteers)—commonly referred to as the Tonton Macoute after a Haitian Creole bogeyman—to extend and bolster support for the regime in the countryside. The Macoute, which by 1961 was twice as big as the army, never developed into a real military force but was more than just a secret police.[20]

In the early years of his rule, Duvalier was able to take advantage of the strategic weaknesses of his powerful opponents, mostly from the mulatto elite. These weaknesses included their inability to coordinate their actions against the regime, whose power had grown increasingly stronger.[21]

In the name of nationalism, Duvalier expelled almost all of Haiti’s foreign-born bishops, an act that earned him excommunication from the Catholic Church.[11] In 1966, he persuaded the Holy See to allow him permission to nominate the Catholic hierarchy for Haiti.[22] No longer was Haiti under the grip of the minority rich mulattoes, protected by the military and supported by the church; Duvalier now exercised more power in Haiti than ever.

Heart attack and Barbot affair[edit]

On 24 May 1959, Duvalier suffered a massive heart attack, possibly due to an insulin overdose; he had been a diabetic since early adulthood and also suffered from heart disease and associated circulatory problems. During the heart attack, he was comatose for nine hours.[6]:81–82 His physician believed that he suffered neurological damage during these events, which harmed his mental health.[6]:82

While recovering, Duvalier left power in the hands of Clément Barbot, leader of the Tonton Macoute. Upon his return to work, Duvalier accused Barbot of trying to supplant him as president and had him imprisoned. In April 1963, Barbot was released and began plotting to remove Duvalier from office by kidnapping his children. The plot failed and Duvalier subsequently ordered a nationwide search for Barbot and his fellow conspirators. During the search, Duvalier was told that Barbot had transformed himself into a black dog, which prompted Duvalier to order that all black dogs in Haiti be put to death. The Tonton Macoute captured then killed Barbot in July 1963. In other incidents, Duvalier ordered the head of an executed rebel packed in ice and brought to him so he could commune with the dead man’s spirit.[23]Peepholes were carved into the walls of the interrogation chambers, through which Duvalier watched Haitian detainees being tortured and submerged in baths of sulfuric acid; sometimes, he was in the room during the tortures.[24]

Constitutional changes[edit]

In 1961, Duvalier began violating the provisions of the 1957 constitution: first he replaced the bicameral legislature with a unicameral body. Then he called a new presidential election in which he was the sole candidate, though his term was to expire in 1963 and the constitution prohibited re-election. The election was flagrantly rigged; the official tally showed 1,320,748 “yes” votes for another term for Duvalier, with none opposed.[10] Upon hearing the results, he proclaimed, “I accept the people’s will. . . . As a revolutionary, I have no right to disregard the will of the people".[6]:85[16] The New York Times commented, “Latin America has witnessed many fraudulent elections throughout its history but none has been more outrageous than the one which has just taken place in Haiti”.[6]:85 On 14 June 1964, a constitutional referendum made Duvalier “President for Life”, a title previously held by seven Haitian presidents. This referendum was also blatantly rigged; an implausible 99.9% voted in favor, which should have come as no surprise since all the ballots were premarked “yes”.[6]:96–97[10] The new document granted Duvalier—or Le Souverain, as he was called—absolute powers as well as the right to name his successor. The identity of the 0.1% is still unknown.

Foreign relations[edit]

His relationship with the United States proved difficult. In his early years, Duvalier rebuked the United States for its friendly relations with Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo (assassinated in 1961) while ignoring Haiti. The Kennedy administration (1961–1963) was particularly disturbed by Duvalier’s repressive and authoritarian rule and allegations that he misappropriated aid money—at the time a substantial part of the Haitian budget—and a U.S. Marine Corps mission to train the Tonton Macoute. The U.S. thus halted most of its economic assistance in mid-1962, pending stricter accounting procedures, with which Duvalier refused to comply. Duvalier publicly renounced all aid from Washington on nationalist grounds, portraying himself as a “principled and lonely opponent of domination by a great power”.[10]:234

Duvalier misappropriated millions of dollars of international aid, including US$?15 million annually from the United States.[25]:50–51 He transferred this money to personal accounts. Another of Duvalier’s methods of obtaining foreign money was to gain foreign loans, including US$?4 million from Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.[25]:47–48

After the assassination of John F. Kennedy in November 1963, which Duvalier later claimed resulted from a curse that he had placed on Kennedy,[26] the U.S. eased its pressure on Duvalier, grudgingly accepting him as a bulwark against communism.[10][27] Duvalier attempted to exploit tensions between the U.S. and Cuba, emphasizing his anti-communist credentials and Haiti’s strategic location as a means of winning U.S. support:

| Address | |

| Phone | ,, |

| Fax |